Growers/Vintners for Responsible Agriculture

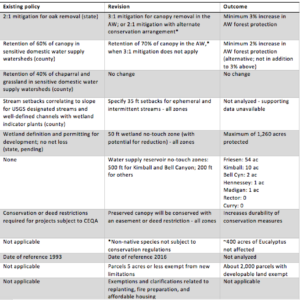

As part two of GVfRA’s discussion of recent changes to Napa County’s Water Quality and Tree Protection Ordinance, this article provides perspectives and specifics related to new rules. Amendments recently adopted by the Board of Supervisors will go into effect in May 2019. A study by Amber Manfree, PhD, determined that newly adopted rules will reduce total developable area by about 3 percent, leaving over 30,000 acres of trees open to deforestation in Napa County.

During the ordinance adoption process, Napa County Board of Supervisors and Planning Commissioners received comments from stakeholders, property rights advocates, subject area experts, and the general public. Numerous calls were made for science-based decision-making. Commenters including Ross Middlemiss on behalf of The Center for Biological Diversity, California Wildlife Foundation and California Oaks, biologist Jake Ruygt, and others pointed to scientific research that suggests conserving Napa’s wildlands has tremendous benefits for biodiversity, climate change buffering and adaptation, and water security.

In the late 1900s, Napa Valley saw a shift from prunes, walnuts, and other crops to wine grapes. With the Napa Valley floor effectively planted out, large-scale vineyard developments now typically require removal of wildlands. In a time of increasing awareness of the related threats of climate change and biodiversity loss, bulldozing of wildlands is far less socially acceptable than it once was. At the same time, wildland conversion is often the only realistic way for new wine growers to enter the Napa market. But how much land are we really talking about, and what may the effects of newly adopted rules be?

Most remaining undeveloped land is in the 442,200 acre Agricultural Watershed (AW) Zoning District, which encompasses mountainous areas surrounding Napa Valley. There are a total of about 199,300 forested acres in the AW. About 50 percent of the AW has slopes over 30 percent, which are rarely permitted for development due to Napa County’s Hillside Ordinance and concerns about erosion. Prior to recent amendments, there were about 69,000 acres available for development in the AW. About half of this developable area, or 34,400 acres, is forested. Over 70 percent of those trees are oaks. The remainder of the non-forested area is covered in grasslands, chaparral, and other land cover types.

Changes to existing protections may reduce at-risk forest to 28,700 acres in the AW. These rules may yield an overall increase of 5,700 acres, or three percent, in protection of AW forests beyond existing rules.

Will a two to three percent reduction in development potential meaningfully slow or prevent wildland conversion in Napa County? Typically it would not.

Grassland and chaparral are already the most commonly converted plant community types. They have essentially no protection from development other than slope-related rules of the Hillside Ordinance, and will not be receiving any increase in protection with new rules. There are over 40,400 at-risk acres of chaparral and grassland county-wide, in addition to the 28,700 acres of at-risk forest in the AW and over 1,500 acres of at-risk forest in other zones, for a grand total of over 70,000 at-risk acres.

Planning staff have a wide range of conservation options with the Water Quality and Tree Protection Ordinance, and they have considerable latitude in their per-parcel interpretation of the rule. For this reason, and because sensitive species were not accounted for, actual conservation may be higher than estimated. However, few existing wildland conversion projects built since the adoption of Napa’s Hillside Ordinance in 1993 have conserved substantially more area than legal minimums required by state and local rules. As new projects undergo the planning process, applications of the ordinance will become clearer.

The most significant effects of new rules may be (1) for wetlands; though the forthcoming California Wetland Riparian Area Protection Policy will likely overlap some, (2) in formalizing existing planning department practices as with ephemeral stream setbacks, and (3) in requiring that conservation lands be restricted legally more often.